Wizard of Oz Writeup Kills Again

Original championship folio | |

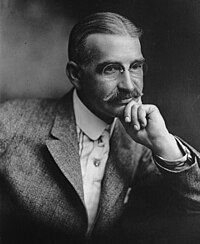

| Author | L. Frank Baum |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | W. Westward. Denslow |

| Country | The states |

| Language | English |

| Serial | The Oz books |

| Genre | Fantasy, children's novel |

| Publisher | George M. Hill Visitor |

| Publication appointment | May 17, 1900 |

| OCLC | 9506808 |

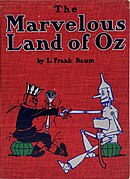

| Followed by | The Marvelous Land of Oz |

The Wonderful Magician of Oz is an American children's novel written by writer L. Frank Baum and illustrated by W. West. Denslow.[i] The first novel in the Oz books, the Kansas farm girl named Dorothy ends up in the magical Land of Oz after she and her pet domestic dog Toto are swept away from their home past a tornado.[ii] Upon her inflow in Oz, she learns she cannot return home until she has destroyed the Wicked Witch of the Due west.[3]

The book was commencement published in the United states in May 1900 by the George M. Hill Company.[4] In Jan 1901, the publishing company completed printing the first edition, a total of ten,000 copies, which apace sold out.[4] Information technology had sold 3 one thousand thousand copies past the time information technology entered the public domain in 1956. It was often reprinted under the title The Wizard of Oz , which is the title of the successful 1902 Broadway musical adaptation too equally the archetype 1939 live-action motion-picture show.[5] [6]

The ground-breaking success of both the original 1900 novel and the 1902 Broadway musical prompted Baum to write 13 additional Oz books which serve equally official sequels to the first story. Over a century later, the book is one of the best-known stories in American literature, and the Library of Congress has declared the work to be "America's greatest and all-time-loved homegrown fairytale."[7]

Publication [edit]

(Left) 1900 first edition embrace, published by the George 1000. Hill Company, Chicago, New York; (right) the 1900 edition original back cover.

50. Frank Baum's story was published by George M. Colina Visitor.[iv] The commencement edition had a printing of 10,000 copies and was sold in advance of the publication engagement of September i, 1900.[4] On May 17, 1900, the first re-create came off the press; Baum assembled information technology by hand and presented information technology to his sister, Mary Louise Baum Brewster. The public saw it for the starting time time at a volume off-white at the Palmer Business firm in Chicago, July 5–xx. Its copyright was registered on August 1; full distribution followed in September.[8] By Oct 1900, information technology had already sold out and the 2nd edition of fifteen,000 copies was almost depleted.[four]

In a letter to his brother, Baum wrote that the volume's publisher, George M. Colina, predicted a sale of about 250,000 copies. In spite of this favorable conjecture, Hill did non initially predict that the volume would exist phenomenally successful. He agreed to publish the book only when the manager of the Chicago Thou Opera House, Fred R. Hamlin, committed to making it into a musical stage play to publicize the novel.

The play The Wizard of Oz debuted on June 16, 1902. It was revised to suit developed preferences and was crafted as a "musical extravaganza," with the costumes modeled after Denslow'due south drawings. When Hill's publishing visitor became broke in 1901,[9] the Indianapolis-based Bobbs-Merrill Visitor resumed publishing the novel.[10] [9] Past 1938, more than 1 million copies of the book had been printed.[eleven] By 1956, sales had grown to three million copies.

Plot [edit]

Dorothy catches Toto by the ear every bit their house is caught up in a whirlwind. First edition illustration by W. W. Denslow.

Dorothy is a young girl who lives with her Aunt Em, Uncle Henry, and dog, Toto, on a farm on the Kansas prairie. 1 24-hour interval, she and Toto are defenseless upwards in a cyclone that deposits them and the farmhouse into Munchkin State in the magical Land of Oz. The falling firm has killed the Wicked Witch of the Due east, the evil ruler of the Munchkins. The Skillful Witch of the North arrives with three grateful Munchkins and gives Dorothy the magical silverish shoes that one time belonged to the Wicked Witch. The Good Witch tells Dorothy that the only way she tin can return home is to follow the yellow brick route to the Emerald City and ask the great and powerful Wizard of Oz to help her. As Dorothy embarks on her journey, the Good Witch of the North kisses her on the forehead, giving her magical protection from harm.

On her way down the yellow brick road, Dorothy attends a banquet held by a Munchkin named Boq. The adjacent mean solar day, she frees a Scarecrow from the pole on which he is hanging, applies oil from a can to the rusted joints of a Tin Woodman, and meets a Cowardly Lion. The Scarecrow wants a brain, the Tin Woodman wants a heart, and the Lion wants courage, then Dorothy encourages them to journey with her and Toto to the Emerald City to inquire for aid from the Wizard.

After several adventures, the travelers arrive at the Emerald City and run into the Guardian of the Gates, who asks them to wear light-green tinted spectacles to keep their optics from being blinded by the city's brilliance. Each one is called to see the Wizard. He appears to Dorothy as a giant head, to the Scarecrow as a lovely lady, to the Tin can Woodman every bit a terrible fauna, and to the Lion equally a ball of fire. He agrees to help them all if they kill the Wicked Witch of the West, who rules over Winkie Country. The Guardian warns them that no 1 has ever managed to defeat the witch.

The Wicked Witch of the West sees the travelers approaching with her 1 telescopic centre. She sends a pack of wolves to tear them to pieces, merely the Tin can Woodman kills them with his axe. She sends a flock of wild crows to peck their eyes out, merely the Scarecrow kills them by twisting their necks. She summons a swarm of black bees to sting them, but they are killed while trying to sting the Tin Woodman while the Scarecrow'southward straw hides the others. She sends a dozen of her Winkie slaves to assault them, but the Panthera leo stands firm to repel them. Finally, she uses the power of her Golden Cap to send the Winged Monkeys to capture Dorothy, Toto, and the Lion, unstuff the Scarecrow, and paring the Tin can Woodman. Dorothy is forced to become the witch's personal slave, while the witch schemes to steal her silvery shoes.

The Wicked Witch melts. First edition analogy by W. West. Denslow.

The witch successfully tricks Dorothy out of i of her silverish shoes. Angered, she throws a bucket of h2o at the witch and is shocked to encounter her melt away. The Winkies rejoice at being freed from her tyranny and help restuff the Scarecrow and mend the Tin Woodman. They ask the Can Woodman to become their ruler, which he agrees to exercise after helping Dorothy return to Kansas. Dorothy finds the witch's Golden Cap and summons the Winged Monkeys to carry her and her friends dorsum to the Emerald City. The King of the Winged Monkeys tells how he and his band are leap by an enchantment to the cap by the sorceress Gayelette from the North, and that Dorothy may utilize it to summon them two more times.

When Dorothy and her friends run into the Wizard once again, Toto tips over a screen in a corner of the throne room that reveals the Sorcerer, who sadly explains he is a braggadocio—an ordinary quondam man who, by a hot air balloon, came to Oz long ago from Omaha. He provides the Scarecrow with a head full of bran, pins, and needles ("a lot of bran-new brains"), the Can Woodman with a silk heart stuffed with sawdust, and the King of beasts a potion of "courage". Their faith in his power gives these items a focus for their desires. He decides to take Dorothy and Toto home and so go back to Omaha in his balloon. At the ship-off, he appoints the Scarecrow to dominion in his stead, which he agrees to exercise after helping Dorothy return to Kansas. Toto chases a kitten in the crowd and Dorothy goes after him, but the ropes holding the balloon break and the Magician floats away.

Dorothy summons the Winged Monkeys and tells them to carry her and Toto home, simply they explain they can't cross the desert surrounding Oz. The Soldier with the Green Whiskers informs Dorothy that Glinda, the Practiced Witch of the South may exist able to help her return dwelling, so the travelers begin their journeying to run into Glinda's castle in Quadling Country. On the way, the Panthera leo kills a giant spider who is terrorizing the animals in a forest. They ask him to become their king, which he agrees to practise subsequently helping Dorothy return to Kansas. Dorothy summons the Winged Monkeys a third time to fly them over a loma to Glinda's castle.

Glinda greets them and reveals that Dorothy'south silver shoes can have her anywhere she wishes to become. She embraces her friends, all of whom will exist returned to their new kingdoms through Glinda'southward three uses of the Golden Cap: the Scarecrow to the Emerald City, the Tin can Woodman to Winkie Country, and the Lion to the forest; after which the cap will be given to the Male monarch of the Winged Monkeys, freeing him and his ring. Dorothy takes Toto in her arms, knocks her heels together three times, and wishes to return home. Instantly, she begins whirling through the air and rolling on the grass of the Kansas prairie, up to the farmhouse, though the silverish shoes fall off her feet en route and are lost in the Deadly Desert. She runs to Aunt Em, saying "I'k so glad to be home once again!"

Illustrations [edit]

The volume was illustrated by Baum'south friend and collaborator West. West. Denslow, who also co-held the copyright. The design was lavish for the time, with illustrations on many pages, backgrounds in unlike colors, and several color plate illustrations.[12] The typeface featured the newly designed Monotype Onetime Style. In September 1900, The Grand Rapids Herald wrote that Denslow's illustrations are "quite as much of the story as in the writing". The editorial opined that had it not been for Denslow's pictures, the readers would be unable to moving-picture show precisely the figures of Dorothy, Toto, and the other characters.[13]

Denslow's illustrations were so well known that merchants of many products obtained permission to use them to promote their wares. The forms of the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, the Cowardly King of beasts, the Wizard, and Dorothy were made into safety and metallic sculptures. Costume jewelry, mechanical toys, and soap were also designed using their figures.[xiv] The distinctive look of Denslow's illustrations led to imitators at the fourth dimension, most notably Eva Katherine Gibson'due south Zauberlinda, the Wise Witch, which mimicked both the typography and the illustration design of Oz.[15]

A new edition of the volume appeared in 1944, with illustrations by Evelyn Copelman.[16] [17] Although information technology was claimed that the new illustrations were based on Denslow's originals, they more closely resemble the characters as seen in the famous 1939 flick version of Baum's book.[18]

Creative inspiration [edit]

Baum's personal life [edit]

According to Baum'south son, Harry Neal, the author had often told his children "whimsical stories before they became material for his books."[xix] Harry called his begetter the "swellest man I knew," a man who was able to give a decent reason as to why black birds cooked in a pie could afterwards go out and sing.[19]

Many of the characters, props, and ideas in the novel were drawn from Baum'due south personal life and experiences.[20] Baum held different jobs, moved a lot, and was exposed to many people, and then the inspiration for the story could have been taken from many unlike aspects of his life.[20] In the introduction to the story, Baum writes that "it aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heart-aches and nightmares are left out."[21]

Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman [edit]

As a child, Baum oftentimes had nightmares of a scarecrow pursuing him beyond a field.[22] Moments before the scarecrow'south "ragged hay fingers" nearly gripped his neck, it would fall apart earlier his eyes. Decades later, as an developed, Baum integrated his tormentor into the novel as the Scarecrow.[23] In the early on 1880s, Baum'due south play Matches was existence performed when a "flicker from a kerosene lantern sparked the rafters", causing the Baum opera house to be consumed by flames. Scholar Evan I. Schwartz suggested that this might have inspired the Scarecrow's severest terror: "In that location is only one affair in the world I am afraid of. A lighted match."[24]

According to Baum'southward son Harry, the Tin Woodman was built-in from Baum's attraction to window displays. He wished to make something captivating for the window displays, and then he used an eclectic assortment of scraps to craft a striking effigy. From a wash-boiler he made a trunk, from bolted stovepipes he made arms and legs, and from the lesser of a saucepan he made a face. Baum and so placed a funnel hat on the figure, which ultimately became the Tin Woodman.[25]

Dorothy, Uncle Henry, and the Witches [edit]

Baum'due south wife Maud Gage frequently visited their newborn niece, Dorothy Louise Gage, whom she adored every bit the daughter she never had. The baby became gravely sick and died aged five months in Bloomington, Illinois on Nov eleven, 1898, from "congestion of the brain". Maud was devastated.[26] To assuage her distress, Frank made his protagonist of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz a girl named Dorothy, and he dedicated the book to his married woman.[27] The baby was buried at Evergreen Cemetery, where her gravestone has a statue of the graphic symbol Dorothy placed next to it.[28]

Decades afterward, Jocelyn Burdick—the girl of Baum'south other niece Magdalena Carpenter and a former Democratic U.S. Senator from North Dakota—asserted that her mother also partly inspired the character of Dorothy.[29] Burdick claimed that her great-uncle spent "considerable fourth dimension at the Сarpenter homestead... and became very attached to Magdalena."[29] Burdick has reported many similarities between her mother'southward homestead and the farm of Aunt Em and Uncle Henry.[29]

Uncle Henry was modeled after Henry Cuff, Baum'due south begetter-in-police force. Bossed around by his wife Matilda, Henry rarely dissented with her. He flourished in business, though, and his neighbors looked up to him. Likewise, Uncle Henry was a "passive merely hard-working man" who "looked stern and solemn, and rarely spoke".[xxx] The witches in the novel were influenced by witch-hunting research gathered by Matilda Cuff. The stories of brutal acts against accused witches scared Baum. Two key events in the novel involve wicked witches who meet their death through metaphorical ways.[31]

The Emerald City and the Land of Oz [edit]

The Emerald City (Denslow, 1900)

In 1890, Baum lived in Aberdeen, Southward Dakota during a drought, and he wrote a witty story in his "Our Landlady" column in Aberdeen's The Sabbatum Pioneer most a farmer who gave green goggles to his horses, causing them to believe that the forest fries that they were eating were pieces of grass.[32] Similarly, the Wizard fabricated the people in the Emerald City habiliment green goggles then that they would believe that their metropolis was built from emeralds.[33]

During Baum's short stay in Aberdeen, the broadcasting of myths about the plentiful West continued. However, the West, instead of being a wonderland, turned into a wasteland because of a drought and a depression. In 1891, Baum moved his family from South Dakota to Chicago. At that time, Chicago was getting ready for the Earth's Columbian Exposition in 1893. Scholar Laura Barrett stated that Chicago was "considerably more akin to Oz than to Kansas". Later discovering that the myths about the West's incalculable riches were baseless, Baum created "an extension of the American borderland in Oz". In many respects, Baum's creation is similar to the actual frontier salve for the fact that the W was still undeveloped at the time. The Munchkins Dorothy encounters at the commencement of the novel correspond farmers, as practise the Winkies she later meets.[34]

Local fable has information technology that Oz, too known every bit the Emerald City, was inspired by a prominent castle-like edifice in the community of Castle Park near Holland, Michigan, where Baum lived during the summer. The yellowish brick route was derived from a road at that time paved by yellow bricks, located in Peekskill, New York, where Baum attended the Peekskill Armed forces Academy. Baum scholars oftentimes refer to the 1893 Chicago World'due south Off-white (the "White Metropolis") equally an inspiration for the Emerald Metropolis. Other legends propose that the inspiration came from the Hotel Del Coronado nigh San Diego, California. Baum was a frequent guest at the hotel and had written several of the Oz books there.[35] In a 1903 interview with The Publishers' Weekly,[36] Baum said that the name "Oz" came from his file cabinet labeled "O–Z".[37] [22]

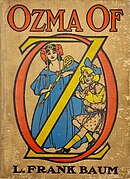

Some critics have suggested that Baum's Oz may accept been inspired past Australia. Australia is oftentimes colloquially spelled or referred to as "Oz". Furthermore, in Ozma of Oz (1907), Dorothy gets back to Oz equally the result of a storm at sea while she and Uncle Henry are traveling by ship to Australia. Similar Australia, Oz is an island continent somewhere to the due west of California with inhabited regions bordering on a peachy desert. Baum perhaps intended Oz to be Australia or a magical state in the centre of the great Australian desert.[38]

Alice'south Adventures in Wonderland [edit]

In add-on to being influenced by the fairy-tales of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen,[39] Baum was significantly influenced by English author Lewis Carroll's 1865 novel Alice'south Adventures in Wonderland.[forty] Although Baum plant the plot of Carroll's novel to be incoherent, he identified the book'due south source of popularity as Alice herself—a kid with whom younger readers could place, and this influenced Baum'due south option of Dorothy as his protagonist.[39]

Baum also was influenced by Carroll'southward views that all children's books should be lavishly illustrated, be pleasurable to read, and not contain any moral lessons.[41] During the Victorian era, Carroll had rejected the popular expectation that children'south books must be saturated with moral lessons and instead he contended that children should be immune to be children.[42]

Although influenced by Carroll's distinctly English piece of work, Baum still sought to create a story that had recognizable American elements, such as farming and industrialization.[41] Consequently, Baum combined the conventional features of a fairy tale such equally witches and wizards with well-known fixtures in his young readers' Midwestern lives such as scarecrows and cornfields.[43]

Influence of Denslow [edit]

The original illustrator of the novel, W. W. Denslow, aided in the development of Baum's story and profoundly influenced the way information technology has been interpreted.[22] Baum and Denslow had a close working relationship and worked together to create the presentation of the story through the images and the text.[22] Colour is an important element of the story and is present throughout the images, with each chapter having a unlike colour representation. Denslow besides added characteristics to his drawings that Baum never described. For example, Denslow drew a firm and the gates of the Emerald Metropolis with faces on them.

In the afterward Oz books, John R. Neill, who illustrated all the sequels, continued to use elements from Denslow's earlier illustrations, including faces on the Emerald City's gates.[44] Some other aspect is the Tin Woodman's funnel hat, which is not mentioned in the text until afterwards books merely appears in most artists' interpretation of the character, including the stage and film productions of 1902–09, 1908, 1910, 1914, 1925, 1931, 1933, 1939, 1982, 1985, 1988, 1992, and others. One of the earliest illustrators not to include a funnel hat was Russell H. Schulz in the 1957 Whitman Publishing edition—Schulz depicted him wearing a pot on his caput. Libico Maraja's illustrations, which first appeared in a 1957 Italian edition and accept also appeared in English language-language and other editions, are well known for depicting him bareheaded.

Allusions to 19th-century America [edit]

Many decades subsequently its publication, Baum'southward work gave rising to a number of political interpretations, peculiarly in regards to the 19th-century Populist movement in the United States.[45] In a 1964 American Quarterly article titled "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism",[46] educator Henry Littlefield posited that the book served an apologue for the late 19th-century bimetallism fence regarding monetary policy.[47] [48] Littlefield's thesis achieved some back up but was widely criticized past others.[49] [50] [51] Other political interpretations soon followed. In 1971, historian Richard J. Jensen theorized in The Winning of the Midwest that "Oz" was derived from the mutual abridgement for "ounce", used for denoting quantities of gold and argent.[52]

Critical response [edit]

This concluding story of The Magician is ingeniously woven out of commonplace fabric. It is, of grade, an extravaganza, simply will surely exist found to entreatment strongly to child readers as well as to the younger children, to whom it volition be read by mothers or those having charge of the entertaining of children. There seems to be an inborn beloved of stories in child minds, and one of the most familiar and pleading requests of children is to be told another story.

The cartoon as well as the introduced color work vies with the texts fatigued, and the result has been a book that rises far above the boilerplate children'due south volume of today, high equally is the present standard....

The book has a bright and joyous atmosphere, and does non dwell upon killing and deeds of violence. Enough stirring adventure enters into it, all the same, to flavor it with zest, and it will indeed be strange if there be a normal child who volition not savour the story.

The New York Times, September 8, 1900 [53]

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz received positive critical reviews upon release. In a September 1900 review, The New York Times praised the novel, writing that it would appeal to kid readers and to younger children who could not read yet. The review also praised the illustrations for being a pleasant complement to the text.[53]

During the subsequent decades afterwards the novel's publication in 1900, information technology received trivial critical analysis from scholars of children's literature. Lists of suggested reading published for juvenile readers never contained Baum's work,[54] and his works were rarely assigned in classrooms. [55] This lack of interest stemmed from the scholars' misgivings about fantasy, as well as to their conventionalities that lengthy series had little literary merit.[54]

It frequently came under fire in later decades. In 1957, the director of Detroit's libraries banned The Wonderful Magician of Oz for having "no value" for children of today, for supporting "negativism", and for bringing children's minds to a "cowardly level". Professor Russel B. Nye of Michigan Land University countered that "if the message of the Oz books—beloved, kindness, and unselfishness make the globe a meliorate identify—seems of no value today", then possibly the time is ripe for "reassess[ing] a expert many other things too the Detroit library'due south approved list of children's books".[56]

In 1986, seven Fundamentalist Christian families in Tennessee opposed the novel's inclusion in the public school syllabus and filed a lawsuit.[57] They based their opposition to the novel on its depicting benevolent witches and promoting the belief that integral man attributes were "individually developed rather than God-given".[57] Ane parent said, "I practice not desire my children seduced into godless supernaturalism".[58] Other reasons included the novel'south instruction that females are equal to males and that animals are personified and can speak. The gauge ruled that when the novel was being discussed in form, the parents were allowed to have their children leave the classroom.[59]

In Apr 2000, the Library of Congress declared The Wonderful Sorcerer of Oz to be "America's greatest and best-loved homegrown fairytale", also naming it the first American fantasy for children and one of the most-read children's books.[7] Leonard Everett Fisher of The Horn Book Magazine wrote in 2000 that Oz has "a timeless bulletin from a less complex era, and it continues to resonate". The challenge of valuing oneself during impending arduousness has not, Fisher noted, lessened during the prior 100 years.[threescore] 2 years afterwards, in a 2002 review, Bill Delaney of Salem Printing praised Baum for giving children the opportunity to discover magic in the mundane things in their everyday lives. He further commended Baum for pedagogy "millions of children to love reading during their crucial formative years".[43] In 2012 it was ranked number 41 on a list of the top 100 children'due south novels published by School Library Journal.[61]

Editions [edit]

After George K. Colina'south bankruptcy in 1902, copyright in the book passed to the Bowen-Merrill Visitor of Indianapolis.[ix] The visitor published most of Baum'south other books from 1901 to 1903 (Male parent Goose, His Book (reprint), The Magical Monarch of Mo (reprint), American Fairy Tales (reprint), Dot and Tot of Merryland (reprint), The Master Primal, The Army Alphabet, The Navy Alphabet, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, The Enchanted Island of Yew, The Songs of Father Goose) initially under the title The New Wizard of Oz. The discussion "New" was apace dropped in subsequent printings, leaving the at present-familiar shortened title, "The Wizard of Oz," and some small-scale textual changes were added, such as to "yellow daises," and changing a chapter title from "The Rescue" to "How the Four Were Reunited." The editions they published lacked nigh of the in-text colour and colour plates of the original. Many toll-cutting measures were implemented, including removal of some of the color press without replacing it with blackness, printing nothing rather than the beard of the Soldier with the Green Whiskers.

When Baum filed for defalcation after his critically and popularly successful moving picture and phase product The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays failed to make back its production costs, Baum lost the rights to all of the books published by what was at present chosen Bobbs-Merrill, and they were licensed to the M. A. Donahue Company, which printed them in significantly cheaper "blotting paper" editions with advertising that directly competed with Baum's more contempo books, published by the Reilly & Britton Company, from which he was making his living, explicitly hurting sales of The Patchwork Girl of Oz, the new Oz book for 1913, to boost sales of Wizard, which Donahue called in a full-folio advert in The Publishers' Weekly (June 28, 1913), Baum's "one pre-eminently great Juvenile Book." In a letter to Baum dated Dec 31, 1914, F.K. Reilly lamented that the boilerplate buyer employed past a retail store would not sympathize why he should be expected to spend 75 cents for a copy of Tik-Tok of Oz when he could buy a copy of Wizard for betwixt 33 and 36 cents. Baum had previously written a letter of the alphabet complaining about the Donahue deal, which he did not know most until it was fait accompli, and 1 of the investors who held The Wizard of Oz rights had inquired why the royalty was but five or six cents per copy, depending on quantity sold, which made no sense to Baum.[62]

A new edition from Bobbs-Merrill in 1949 illustrated past Evelyn Copelman, again titled The New Wizard of Oz, paid lip service to Denslow simply was based strongly, apart from the Lion, on the MGM pic. Copelman had illustrated a new edition of The Magical Monarch of Mo 2 years before.[63]

It was non until the book entered the public domain in 1956 that new editions, either with the original color plates, or new illustrations, proliferated.[64] A revised version of Copelman's artwork was published in a Grosset & Dunlap edition, and Reilly & Lee (formerly Reilly & Britton) published an edition in line with the Oz sequels, which had previously treated The Marvelous Land of Oz equally the first Oz book,[65] not having the publication rights to Wizard, with new illustrations past Dale Ulrey.[17] Ulrey had previously illustrated Jack Snow's Jaglon and the Tiger-Faries, an expansion of a Baum short story, "The Story of Jaglon," and a 1955 edition of The Tin Woodman of Oz, though both sold poorly. Subsequently Reilly & Lee editions used Denslow's original illustrations.

Notable more than recent editions are the 1986 Pennyroyal edition illustrated by Barry Moser, which was reprinted past the University of California Printing, and the 2000 The Annotated Wizard of Oz edited by Michael Patrick Hearn (heavily revised from a 1972 edition that was printed in a wide format that allowed for it to be a facsimile of the original edition with notes and additional illustrations at the sides), which was published by W. West. Norton and included all the original color illustrations, besides every bit supplemental artwork by Denslow. Other centennial editions included University Printing of Kansas'due south Kansas Centennial Edition, illustrated by Michael McCurdy with black-and-white illustrations, and Robert Sabuda's popular-upwards book.

Sequels [edit]

Baum wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz without any thought of a sequel. After reading the novel, thousands of children wrote letters to him, requesting that he arts and crafts some other story about Oz. In 1904, amid financial difficulties,[66] Baum wrote and published the showtime sequel, The Marvelous State of Oz,[66] declaring that he grudgingly wrote the sequel to address the popular need.[67] He dedicated the volume to stage actors Fred Stone and David C. Montgomery who played the characters of the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman on phase.[66] Baum wrote large roles for the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman that he deleted from the stage version, The Woggle-Problems, after Montgomery and Rock had aghast at leaving a successful show to do a sequel.

Baum later wrote sequels in 1907, 1908, and 1909. In his 1910 The Emerald City of Oz, he wrote that he could non continue writing sequels because Ozland had lost contact with the rest of the world. The children refused to accept this story, so Baum, in 1913 and every twelvemonth thereafter until his expiry in May 1919, wrote an Oz volume, ultimately writing 13 sequels and one-half a dozen Oz brusk stories.

Baum explained the purpose of his novels in a note he penned to his sister, Mary Louise Brewster, in a copy of Female parent Goose in Prose (1897), his first book. He wrote, "To please a kid is a sweetness and a lovely thing that warms ane's heart and brings its own reward."[68] After Baum'southward death in 1919, Baum's publishers delegated the creation of more sequels to Ruth Plumly Thompson who wrote 21.[43] An original Oz book was published every Christmas between 1913 and 1942.[69] By 1956, 5 million copies of the Oz books had been published in the English language, while hundreds of thousands had been published in eight foreign languages.[x]

Adaptations [edit]

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz has been adapted to other media numerous times.[70] Within several decades afterward its publication, the book had inspired a number of stage and screen adaptations, including a profitable 1902 Broadway musical and three silent films. The most popular cinematic adaptation of the story is The Wizard of Oz, the 1939 film starring Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, and Bert Lahr. The 1939 film was considered innovative because of its special furnishings and revolutionary utilise of Technicolor.[6]

The story has been translated into other languages (at least one time without permission, resulting in Alexander Volkov's The Wizard of the Emerald City novel and its sequels, which were translated into English by Sergei Sukhinov) and adapted into comics several times. Following the lapse of the original copyright, the characters take been adjusted and reused in spin-offs, unofficial sequels, and reinterpretations, some of which have been controversial in their handling of Baum'due south characters.[71]

Influence and legacy [edit]

The Wonderful Magician of Oz has become an established role of multiple cultures, spreading from its early young American readership to becoming known throughout the world. Information technology has been translated or adjusted into nearly every major language, at times existence modified in local variations.[lxx] For case, in some abridged Indian editions, the Tin Woodman was replaced with a horse.[72] In Russian federation, a translation past Alexander Melentyevich Volkov produced half dozen books, The Wizard of the Emerald Urban center serial, which became progressively distanced from the Baum version, as Ellie and her canis familiaris Totoshka travel throughout the Magic Land. The 1939 film adaptation has become a classic of popular culture, shown annually on American television from 1959 to 1998 and then several times a twelvemonth every year beginning in 1999.[73]

In 1974, the story was re-envisioned as The Wiz, a Tony Honor winning musical featuring an all-Black cast and set in the context of modern African-American civilisation.[74] [75] This musical was adapted in 1978 as the feature picture The Wiz, a musical adventure fantasy produced past Universal Pictures and Motown Productions.

There were several Hebrew translations published in State of israel. Equally established in the showtime translation and kept in later ones, the book's Land of Oz was rendered in Hebrew equally Eretz Uz (ארץ עוץ)—i.e. the same as the original Hebrew name of the Biblical Country of Uz, homeland of Task. Thus, for Hebrew readers, this translators' choice added a layer of Biblical connotations absent from the English original.[ citation needed ]

In 2018, "The Lost Art of Oz" projection was initiated to locate and catalogue the surviving original artwork John R. Neill, W. Due west. Denslow, Frank Kramer, Richard "Dirk" Gringhuis, and Dick Martin that was created to illustrate the Oz book series.[76] In 2020, an Esperanto translation of the novel was used by a team of scientists to demonstrate a new method for encoding text in DNA that remains readable afterward repeated copying.[77]

See likewise [edit]

- 1900 in literature

- The Baum Bugle

- Wizard of Oz Club

- The Wiz

- Wicked

- Tin Man (miniseries)

- Lost in Oz (TV series)

- Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Baum & Denslow 1900.

- ^ Greene & Martin 1977, p. 11.

- ^ Greene & Martin 1977, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c d e The New York Times 1900a, p. T13.

- ^ The New York Times 1903, p. 9.

- ^ a b Twiddy 2009.

- ^ a b Library of Congress: Oz Showroom 2000.

- ^ Rogers 2002, pp. 73–94.

- ^ a b c Greene & Martin 1977, p. xiv.

- ^ a b MacFall 1956.

- ^ Verdon 1991.

- ^ Baum 2000, p. xlvii.

- ^ New Fairy Stories 1900.

- ^ Starrett 1954.

- ^ Blossom 1994, p. 9.

- ^ Baum 2000, pp. lv, 7.

- ^ a b Greene & Martin 1977, p. 90.

- ^ University of Minnesota 2006.

- ^ a b Sweetness 1944.

- ^ a b Schwartz 2009, p. xiv.

- ^ Baum 2000, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Greene & Martin 1977, p. ten.

- ^ Gourley 1999, p. 7.

- ^ Schwartz 2009, p. 75.

- ^ Carpenter & Shirley 1992, p. 43.

- ^ Taylor, Moran & Sceurman 2005, p. 208.

- ^ Wagman-Geller 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Elleson 2016.

- ^ a b c Eriksmoen 2020.

- ^ Schwartz 2009, p. 95.

- ^ Schwartz 2009, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Culver 1988, p. 102.

- ^ Hansen 2002, p. 261.

- ^ Barrett 2006, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Fokos 2006.

- ^ Mendelsohn 1986, p. E12.

- ^ Schwartz 2009, p. 273.

- ^ Algeo 1990, pp. 86–89.

- ^ a b Baum 2000, p. 38.

- ^ Baum 2000, p. 38; New Fairy Stories 1900.

- ^ a b Riley 1997, p. 51.

- ^ Berman, Judy (Oct 15, 2020). "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll". Fourth dimension . Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c Delaney 2002.

- ^ Riley 1997, p. 42.

- ^ Ritter 1997; Velde 2002; Rockoff 1990.

- ^ Dighe 2002, p. two.

- ^ Dighe 2002, p. x.

- ^ Littlefield 1964, p. 50.

- ^ Parker 1994, pp. 49–63.

- ^ Sanders 1991, pp. 1042–1050.

- ^ Gardner 2002.

- ^ Jensen 1971, p. 283.

- ^ a b The New York Times 1900b, p. BR12.

- ^ a b Berman 2003, p. 504.

- ^ Culver 1988, p. 98.

- ^ Starrett 1957.

- ^ a b Culver 1988, p. 97.

- ^ Nathanson 1991, p. 301.

- ^ Abrams & Zimmer 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Fisher 2000, p. 739.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (July 7, 2012). "Elevation 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #8 Production. Weblog. School Library Journal (web log.schoollibraryjournal.com).

- ^ Greene 1974, pp. ten–11.

- ^ Stillman 1996.

- ^ Greene & Martin 1977, p. 176.

- ^ Greene & Martin 1977, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Greene & Martin 1977, p. 17.

- ^ Littlefield 1964, pp. 47–48.

- ^ MacFall 1956; Baum & MacFall 1961.

- ^ Watson 2000, p. 112.

- ^ a b Greene & Martin 1977, Preface.

- ^ Baum 2000, pp. ci–cii.

- ^ Rutter 2000.

- ^ Library of Congress: Oz Adaptations 2000.

- ^ Martin 2015.

- ^ Greene & Martin 1977, p. 169.

- ^ "The Story Behind Oz". The Lost Art of Oz.

- ^ Academy of Texas at Austin 2020.

Works cited [edit]

- Abrams, Dennis; Zimmer, Kyle (2010). L. Frank Baum. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN978-one-60413-501-5.

- Algeo, J. (1990). "Australia every bit the State of Oz". American Speech. 65 (one): 86–89. doi:x.2307/455941. JSTOR 455941.

- Barrett, Laura (2006). "From Wonderland to Wasteland: The Wonderful Magician of Oz, The Great Gatsby, and the New American Fairy Tale". Papers on Language & Literature. Southern Illinois University. 42 (two): 150–180. ISSN 0031-1294. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved March vii, 2011.

- Baum, Frank Joslyn; MacFall, Russell P. (1961). To Please a Child. Chicago: Reilly & Lee – via Google Books.

- Baum, Lyman Frank (2000) [1973]. Hearn, Michael Patrick (ed.). The Annotated Sorcerer of Oz: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. New York: Westward. W. Norton & Visitor. ISBN0-393-04992-ii – via Google Books.

- Baum, L. Frank; Denslow, West. W. (1900). The Wonderful Wizard of Oz past L. Frank Baum with Pictures by Due west. Due west. Denslow . Chicago: George Grand. Colina Visitor. Retrieved Feb half-dozen, 2018 – via Cyberspace Archive.

- Berman, Ruth (November 2003). "The Wizardry of Oz". Science Fiction Studies. DePauw University. 30 (3): 504–509. Archived from the original on October ii, 2010. Retrieved Nov 27, 2010.

- Bloom, Harold (1994). Archetype Fantasy Writers. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN0-7910-2204-8.

- "Books and Authors". The New York Times. September 8, 1900b. p. BR12. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- Carpenter, Angelica Shirley; Shirley, Jean (1992). L. Frank Baum: Royal Historian of Oz. Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Grouping. ISBN0-8225-9617-2.

- Culver, Stuart (1988). "What Manikins Want: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows". Representations. Academy of California Press (21): 97–116. doi:10.2307/2928378. JSTOR 2928378.

- Delaney, Beak (March 2002). "The Wonderful Sorcerer of Oz". Salem Press. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved Nov 25, 2010.

- Dighe, Ranjit S. (2002). The Historian's Sorcerer of Oz: Reading Fifty. Frank Baum'south Classic as a Political and Monetary Apologue. Praeger. ISBN978-0-275-97418-3.

- Elleson, Lisa (2016). "Dorothy Louise Gage (June 11, 1898 – Nov 15, 1898)". McLean County Museum of History.

- Eriksmoen, Brusque (July eleven, 2020). "Northward Dakota daughter was the likely inspiration for Dorothy in 'The Wizard of Oz'". The Dickinson Press . Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- Fisher, Leonard Everett (2000). "Future Classics: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz". The Horn Volume Mag. Library Journals. 76 (6): 739. ISSN 0018-5078.

- Fokos, Barbarella (November two, 2006). "Coronado and Oz". San Diego Reader. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014.

- Gardner, Martin; Nye, Russel B. (1994). The Sorcerer of Oz and Who He Was. Eastward Lansing: Michigan State Academy Press – via Google Books.

- Gardner, Todd (2002). "Responses to Littlefield". Archived from the original on April 16, 2013.

- Gourley, Catherine (1999). Media Wizards: A Behind-the-Scene Await at Media Manipulations . Brookfield, CT: 20-First Century Books. ISBN0-7613-0967-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Greene, David L. (Spring 1974). "A Case of Insult". The Baum Bugle. 16 (1): 10–11.

- Greene, David L.; Martin, Dick (1977). The Oz Scrapbook . New York: Random House. ISBN0-394-41054-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Hanff, Peter Eastward.; Greene, Douglas K. (1976). Bibliographia Oziana: A Concise Bibliographical Checklist. The International Wizard of Oz Club. ISBN978-one-930764-03-3.

- Hansen, Bradley A. (2002). "The Fable of the Allegory: The Wizard of Oz in Economics". Journal of Economic Education. Taylor & Francis. 33 (3): 254–264. doi:ten.1080/00220480209595190. JSTOR 1183440. S2CID 15781425.

- Jensen, Richard J. (1971). The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896 . Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing. ISBN0-226-39825-0. LCCN 71-149802 – via Internet Archive.

- Littlefield, Henry M. (1964). "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism". American Quarterly. Johns Hopkins Academy Press. 16 (i): 47–58. doi:10.2307/2710826. JSTOR 2710826. Archived from the original on Baronial 19, 2010.

- Martin, Michel (December xx, 2015). "The Wiz Alive! Defied The Skeptics, Returns for a Second Round". NPR. Archived from the original on Jan 25, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- MacFall, Russell (May xiii, 1956). "He created 'The Wizard': Fifty. Frank Baum, Whose Oz Books Have Gladdened Millions, Was Born 100 Years Ago Tuesday" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Mendelsohn, Ink (May 25, 1986). "Equally a piece of fantasy, Baum's life was a working model". The Spokesman-Review (Sunday ed.). p. E12. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- "Notes and News". The New York Times. October 27, 1900. p. T13. Retrieved September ten, 2021.

- Nathanson, Paul (1991). Over the Rainbow: The Wizard of Oz as a Secular Myth of America . Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN0-7914-0709-8 – via Internet Archive.

- "New Fairy Stories: "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" by Authors of "Begetter Goose."" (PDF). Grand Rapids Herald. September 16, 1900. Archived from the original (PDF) on Feb 3, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- Parker, David B (1994). "The Rise and Autumn of The Wonderful Magician of Oz as a 'Parable on Populism'". Journal of the Georgia Clan of Historians (16): 49–63.

- Riley, Michael O. (1997). Oz and Across: The Fantasy Earth of L. Frank Baum . University of Kansas Press. ISBN0-7006-0832-10 – via Internet Archive.

- Ritter, Gretchen (August 1997). "Silver slippers and a golden cap: L. Frank Baum'south The Wonderful Sorcerer of Oz and historical memory in American politics". Journal of American Studies. 31 (ii): 171–203. doi:x.1017/S0021875897005628.

- Rockoff, Hugh (1990). "The 'Wizard of Oz' every bit a Monetary Apologue". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (four): 739–60. doi:x.1086/261704. S2CID 153606670.

- Rogers, Katharine G. (2002). L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz . New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN0-312-30174-X – via Cyberspace Archive.

- Rutter, Richard (June 2000). Follow the yellow brick road to... (Speech). Indiana Memorial Union, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. Archived from the original on June 10, 2000.

- Sanders, Mitch (July 1991). "Setting the Standards on the Road to Oz". The Numismatist: 1042–1050. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013.

- Schwartz, Evan I. (2009). Finding Oz: how L. Frank Baum discovered the Groovy American story. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN978-0-547-05510-7.

- Starrett, Vincent (May 12, 1957). "L. Frank Baum's Books Live" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Starrett, Vincent (May 2, 1954). "The Best Loved Books" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Stillman, William (Winter 1996). "The Lost Illustrator of Oz (and Mo)". The Baum Bugle. forty (three).

- Sweet, Oney Fred (February 20, 1944). "Tells How Dad Wrote 'Magician of Oz' Stories" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Taylor, Troy; Moran, Mark; Sceurman, Marking (2005). Weird Illinois: Your Travel Guide to Illinois' Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets. Weird US. New York: Sterling Publishing. ISBN0-7607-5943-10.

- "'The Wizard of Oz': A Warm Welcome at the N Pole of Broadway". The New York Times. Jan 21, 1903. p. 9. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- "The Magician of Oz: An American Fairy Tale". Library of Congress. April 21, 2000. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016.

- "To See The Magician: Oz on Stage and Picture". Library of Congress. 2000. Archived from the original on Apr 5, 2011.

- Twiddy, David (September 23, 2009). "'Magician of Oz' goes hi-def for 70th anniversary". The Florida Times-Spousal relationship. Associated Press. Archived from the original on Baronial xiii, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- University of Texas at Austin. "Power of DNA to store information gets an upgrade". Physics.org . Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Velde, Francois R. (2002). "Following the Yellow Brick Road: How the United States Adopted the Gold Standard". Economic Perspectives. 26 (2).

- Verdon, Michael (1991). The Wonderful Magician of Oz. Salem Press.

- Wagman-Geller, Marlene (2008). In one case Once again to Zelda: The Stories Behind Literature's Most Intriguing Dedications. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-399-53462-1.

- Watson, Bruce (2000). "The Amazing Author of Oz". Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. 31 (iii): 112. ISSN 0037-7333.

- "Welcome to the Oz Drove: Pictures past Evelyn Copelman". Children'due south Literature Research Collection. University of Minnesota Libraries. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009.

External links [edit]

- Text:

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz at Standard Ebooks

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900 illustrated copy) at Project Gutenberg

- The Wonderful Magician of Oz (1900 illustrated copy), Publisher'due south green and red illustrated cloth over boards; illustrated endpapers. Plate detached. Public Domain – Charles East. Immature Research Library, UCLA. at Net Archive

- Online version of the 1900 first edition on the Library of Congress website.

- Audio:

-

The Wonderful Magician of Oz public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Wonderful Magician of Oz public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Wonderful Wizard of Oz past L. Frank Baum, an unabridged dramatic audio performance at Wired for Books.

-

- Miller, John J. (May eleven, 2006). "Down the Yellow Brick Route of Over-interpretation". The Wall Street Journal . Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- A Long and Dangerous Journey – A History of The Wizard of Oz on the Silvery Screen – Scream-Information technology-Loud.com

- Elleson, Lisa (February 19, 2016). "Dorothy Louise Gage (June 11, 1898 – November 15, 1898)". McLean County Museum of History. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wonderful_Wizard_of_Oz

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Wizard of Oz Writeup Kills Again"

Posting Komentar